Dustborn is written as though its creators heard complaints like “Keep politics out of games” and defiantly went in the opposite direction. It is one of the most overtly political and, more specifically, unapologetically leftist games I’ve ever played, and that uncommonly brazen setup makes its early hours very interesting, but it falls apart in the second half due to monotonous combat and a final few chapters that undo the stronger first half.

A near-future dystopian and plainly fascistic America, fractured into territories following a second civil war, plays the sea-to-shining-sea enemy of a group of bleeding hearts on an undercover road trip to fuel a better tomorrow. With a punk-rock cover story aiding its diverse collection of cast-offs from the new America, and gameplay mechanics akin to a Telltale game, Dustborn checks so many of the boxes of a game I’d normally adore. So it was surprising to me, though ultimately not difficult to explain, when the game left me feeling empty and wanting.

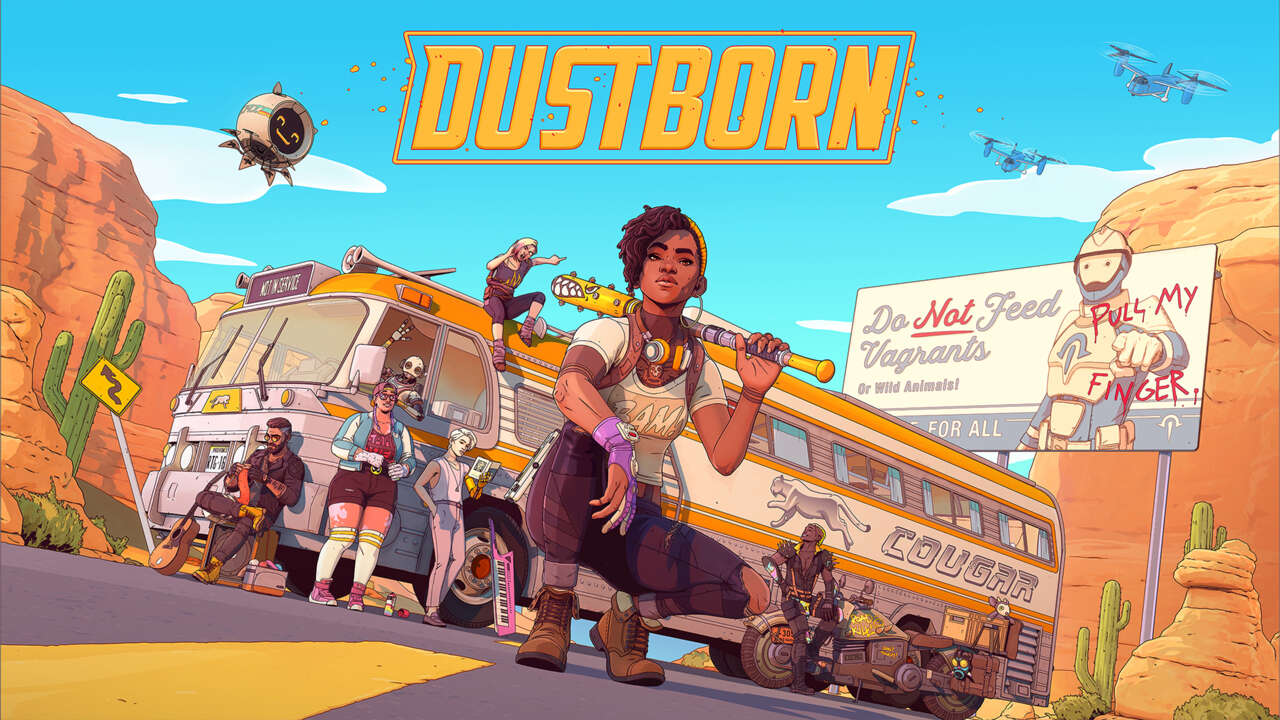

Dustborn’s cel-shaded comic-book art direction is captivating right away, and like the broken world it colors in, it immediately caught my eye. I didn’t mind, at first, when the opening scene featured the four main heroes being rather annoying. I figured this would be their arc, from awkward pals barely dodging the game’s federal force of corrupt cops to defiant leaders toppling tyranny nationwide. I was in for the ride… until I wasn’t.

I can’t say there was one exact moment that turned me away from the group. In hindsight, it feels like it was more of a slow burn. The game’s earliest of its 15 or so hours are heavy on the world-building and I found much of it fascinating. Dustborn plays with an alternate history in which JFK’s wife, Jackie, was killed in Dealey Plaza instead of him. This caused Kennedy to crack down on crime with a new national police force called Justice, which, in a manner reminiscent of the slow-boiled frog, reshaped the country for the worse without it ever being obvious enough to inspire a strong resistance.

As people grew more complacent toward fascist ideals, things culminated in a 2000s-era broadcast event that spread disinformation like a virus, thus expediting the country’s march toward civil war, but also inadvertently creating Anomals (derogatorily called Deviants) who emerged from the event with various new abilities.

It reads like the setup to a cool book I’d love to read, and it works just as well as an adventure game for a while. I love the way the game depicts its a post-truth society. In an early section, it’s explained that disinformation floats in the atmosphere, like a virus on a crowded train, and people can become sick from it if they are exposed. It makes them hostile, mean-spirited, and even drives them to espouse racist, sexist, or other troubling views.

Here is where it becomes obvious–if the game’s earlier way of introducing characters’ pronouns didn’t do it for you–that this is a game made by leftists, about leftists, and very likely for leftists. It is a game that knows when angry young men tweet about wanting no politics in their games, they usually only mean politics with which they don’t agree, and so it feels designed in a way that will knowingly, though not exactly purposely, irritate them with exactly those politics. It doesn’t pull punches in that regard, and surely many anger merchants will take the bait once Dustborn hits stores. Funnily, when you hear fuzzy snippets of disinformation in the air, they’re always regurgitating right-wing talking points on subjects like climate change denial, xenophobia, or even QAnon and Pizzagate.

Though Dustborn does eventually attack the opposite end of the sociopolitical spectrum–you can’t really be a leftist without fighting other leftists, right?–it is, by and large, a story that villainizes right-wing fascists, but notably only pities their supporters. It’s presented as a mirror to our modern-day reality; its view of people who fall for right-wing charlatans is patronizing, but also sincere, as though it’s saying we genuinely ought to feel sorry for such people as the conditions that drove them to be misled are, to some extent, not their fault. It’s definitely a game that could only exist because of the trajectory of the US as it stands today. Despite its alternate history framework, it pulls from real life quite a bit. Portions of the banter during combat even reference some of the dumbest things former President Trump has said.

Though those last few paragraphs may well upset some readers across the aisle, I want to emphasize that all of what I just described are the game’s coolest parts. I not only have no qualms with the team building a world that reflects its politics, but I also greatly appreciate how thoughtful some of it is. Despite the fun it makes of far- (and even not-so-far-) right thinkers, it sincerely strives for empathy and suggests that it’s righteous to help those people come back to reality, rather than leave them to wither away in a cradle of conspiracy theories.

But just because I agree with the game’s politics doesn’t mean it’s a good game.

A lot of Dustborn’s extensive cast of characters focuses primarily on Anomals, including the playable character, Pax, who finds herself equipped with the ability to influence and even hurt people with words. Most of her allies have powers too, like Sai who is extremely strong, or Noam who also has a gift of gab, but theirs leans toward getting someone to calm down, whereas Pax’s are all built on negative emotions that stir people into a fervor. Some of these abilities of the group even lean into therapy terms that have gone mainstream, such as triggering and gaslighting, and a late-game ability actually lets you cancel someone, though each of these abilities is recontextualized for more familiar party-based combat mechanics.

For example, triggering your allies means buffing their damage for a moment, and Pax’s ability to sow discord turns the enemies against each other. You can also hoax enemies, which makes them think they’re on fire, thereby turning reality’s fake news problem into a spell-casting maneuver. This is all pretty clever, but none of it feels good to play.

Pax’s abilities are used in the game’s shoddy combat sections and combined with her allies’ moves on the fly. This is done with real-time third-person combat, though the game pauses so long as you have your ability wheel open, which you unlock by performing enough melee combos in the meantime, giving it all a slight hybrid style akin to some Dragon Age games. The group regularly battles colorful raiders and anonymous secret police as they trek from the west coast, now known as Pacifica, to Nova Scotia, where their subversive mission is meant to conclude.

However, combat feels stiff, and the camera routinely does not track Pax’s movements well. After a few encounters, this created a Pavlovian response in me in which Pax would equip her baseball bat for a combat section, and I would audibly groan. The idea of language being used as a weapon is cool in itself. It fits perfectly with the game’s themes of influence and empathy, but as a third-person action mechanic, it’s one of Dustborn’s weakest parts. I was grateful when, after an early combat scenario, the game asked me if I would rather have more or less combat going forward. I chose the latter, and even then, there was too much, but it’s nice to know it could’ve been worse.

That said, despite my wish not to engage in much combat, the game is hardly better when you’re not. Animations are lifeless even outside of combat, and this is partly why I found it hard to connect with any of the game’s characters. Telltale’s The Walking Dead won awards despite its lifeless character models, but that was 12 years ago. Dustborn runs back similarly janky character expressions and movements to the point that it hurts the actors’ performances, the game’s light puzzle-solving elements, and even just exploring in general. Games like this one that belong in the lineage of those from Telltale and Quantic Dream have, in some cases, moved well beyond such archaic animations by now, but Dustborn is distractingly stuck in the past.

Dustborn frequently adds new outcasts to the group during their travels, but by the end, I was lacking even one who made me emotionally invested. I spent the time getting to know each of them; I checked in with them by the campfire each night, and I gifted them found items, such as fancy new dice for Eli, who spends his days on the road hosting tabletop RPGs with the group.

For the most part, they are well-realized and three-dimensional, but the poor animations are buffed by jarring tonal shifts that alter the game from light-hearted ragtag adventure to super-serious political drama, back and forth the whole way. As a result, I never connected with anybody on the tour bus. Because they routinely squirm out of near-death or imprisonment without consequences, it soon became the norm for me to view their obstacles as little more than time killers, which left me uninvested in their mission.

It’s not that I was left wondering who these characters were by the end. In fact, none of them ever stops talking. The game is so thick with banter that there are rarely any moments of silence. They are always chatting with each other, and as Pax, you are almost always able to jump in and join them whenever you want.

On the one hand, this is impressive, as it feels like you can virtually double the length of the game just by opting into talking to everyone at every opportunity, even if it does conflict with the plot point that the group is always lacking free time. You learn a lot about each of your allies; you shape your relationships with them, all of which determine how the story unfolds and where each character ends up–some may not even survive. So there is at least the illusion of stakes–though a partial replay didn’t suggest major differences in the saga–and there is obvious depth. And yet I just wanted them all to be quiet for a second. Just one second.

They talk so much that other voice lines often cut off their voice lines in an unnatural way because they’ll be blabbering on and on, and you’ll trigger a cutscene or interact with something that halts them mid-sentence so they can say something else instead. It takes a strength of the game and, through subpar implementation, makes it janky. I haven’t heard a cacophony of breathless progressives this grating since I saw Death Cab for Cutie last summer–and I live in Portland.

Dustborn also presented a few technical issues, including a game-breaking bug that caused me to lose all my progress on PC. This bug has since been patched, I’m told, but it seemed not to apply retroactively to my saved data, so while you apparently won’t deal with it post-launch, I had to start the game over after several hours. When I did, the game crashed on me four times in my playthrough, though thankfully the auto-saving feature meant this was just a minor annoyance each time.

The group’s cover story for traversing the hostile state is that they’re a touring punk rock band, and the game even has you perform their shows several times using a Rock Band-style mini-game that is decent and enjoyable, except for its underexplained scoring system. But their music is so sonically tame and decidedly not punk rock beyond the ethos expressed in its lyrics. One of the reasons I was drawn to this game was a sincere desire to hear the original punk rock songs promised within, but there really aren’t any to be found. Instead, they’re a pop act, maybe pop-punk at best, and that missing aggression in their sound was a disappointment. Some of the game’s other lackluster parts are disappointing, but this one is confusing, first and foremost.

The band’s incendiary lyrics should likely get them locked up in such a hostile land, but the only time this ever came up in my playthrough was when a Justice cop passively warned me that folks in America don’t take kindly to such songs–even though the song was overtly about progressives outliving their political enemies and inheriting a world they can then make better. It seemed like I should get more than a slap on the wrist since the story made a point of telling me how unforgiving the cops are.

That’s an excellent example of how it all unravels, too, as it illustrates the chasm between the setup and the execution. The history that Dustborn introduces is engrossing at first. I read every document I could, down to the small signs taped to a fridge, or the packaging on the jerky; I interacted with every poster or book to see what other signs of its alternate history I could find. And in its comic-book art style, it all looked as interesting as its setting first sounded.

But over the course of the game, and particularly in its final few chapters, a story already soaked in metaphors–some better than others–positively drowns in them. It eventually goes so far off the rails that its thoughtful early chapters feel written by entirely different human beings. I’d be more forgiving of this narratively chaotic final act if I were attached to the characters–I like Lost Season 6, after all. In Lost’s case, the events could be silly, but at least I’d have my people. In Dustborn, however, I never really had them to begin with, so I was left with nothing to latch onto. Dustborn’s moral compass points to true north, but before long, both its story and gameplay go south.