Konami is trying to figure out how to make Silent Hill games again. After more than a decade away from the series (and arguably many more years since a good one), multiple new Silent Hill projects have recently debuted or soon shall. Silent Hill devotees like me often wonder whether the publisher can recapture the magic of the series’ early games. But even if it can’t, at least we have Hollowbody. Made by a single person, Hollowbody sometimes goes too far past being a homage, but most of the time, it stands apart as a memorable entry in the crowded space of horror games drumming up the past.

This year, Hollowbody is the closest thing you’ll find to Silent Hill 2 that isn’t Bloober Team’s forthcoming remake. Its solo developer, Nathan Hamley (working under the studio name Headware Games), admits his love for the series is the driving force in creating Hollowbody, and there are times when that adoration is even too obvious. Everything from how you explore its world and unlock new pathways by solving tricky puzzles to how you fight enemies and even unlock multiple endings all feel pulled from the PS2 classic. An early section of the third-person survival-horror game takes place in corridors that are so similar to Silent Hill 2’s hospital section that it gave me deja vu, and the monsters that stalk just beyond the reach of your flashlight stumble into attacking you like that game’s iconic nurses.

There are even a few moments in which you come upon threateningly deep, dark holes that you drop into without knowing what’s on the other side. One corridor, in particular, prompted me to ask myself the same question that Silent Hill 2’s absurdly long stairwell previously prompted: “How long is this thing?” The callbacks border on copies at times, but Hollowbody doesn’t settle for being merely a clone of the developer’s favorite game–though it is fascinating to see how one person in 2024 can make something very much like a game that required a much larger team just a few decades ago.

Within its mission statement of making a game much like SH2, it’s the things Hollowbody does differently that made me more eager to play it than the many other games like it. I’m not typically nostalgic for games that play and look poorer than modern games tend to, but Hawley captures the essence of that era so well without clinging to the period’s worst aspects. Tank controls, for example, are in the game, but they aren’t in use by default. Masochists will need to toggle them on. Similarly, you do save periodically–at a landline phone rather than a bright red book, mind you–but there are a few autosaves in the game, too, usually before a tougher section.

These modern conveniences do well to reduce frustrations that some similarly minded studios misidentify as valuable, though the legacy pain-point of running along walls, couches, beds, and cabinets seeking interaction points remains, so Hollowbody doesn’t reject every questionable design quirk of its genre. On more than one occasion, I had to retread some areas several times before finding an item I needed to progress, which pulled me out of an otherwise moody scene.

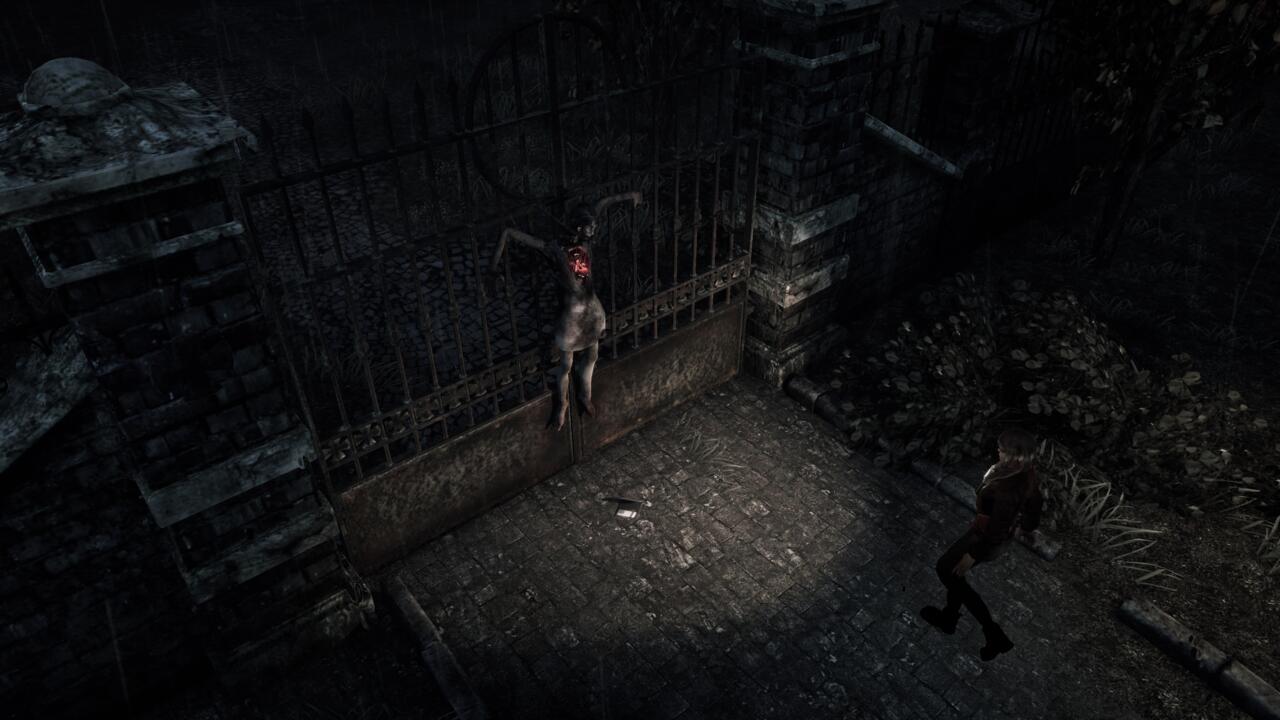

Combat in Hollowbody is very similar to the games that inspired it. That means it’s best to avoid it or use melee weapons if you can, thus saving ammo. Whatever means of defense to which you resort, you’ll often be navigating tight spaces, which make it challenging to flee even after you’ve made up your mind. The game uses a reliable auto-aim system with a green reticle that you can shift from enemy to enemy with ease.

This makes staying alive easier than if you had to rely on guesswork, like some early-2000s horror games asked players to do. I was relieved to find that, despite this helpful mechanic, combat still elicited a welcome sense of dread, partly because the audiovisual cue when you take damage is so jarring that it felt almost like monsters were jumping off the screen in a sense. Enemies close the distance deceptively quickly, and the game’s various melee weapons offer different animations, making them unequal in their reach, attack speed, and effectiveness–I recommend you stick with the guitar.

The game’s atmosphere is its best attribute, with a familiar low hum persisting through most of the story that consistently unnerved me during the four-hour experience. Like great horror developers who have come before, Hamley understands when to lean into the game’s creepy, somber music, and when to let the silence commandeer a scene. Each frame of the game captures the spirit of PS2-era horror games so faithfully that if you knew nothing about the game, you might assume it’s actually from 2001.

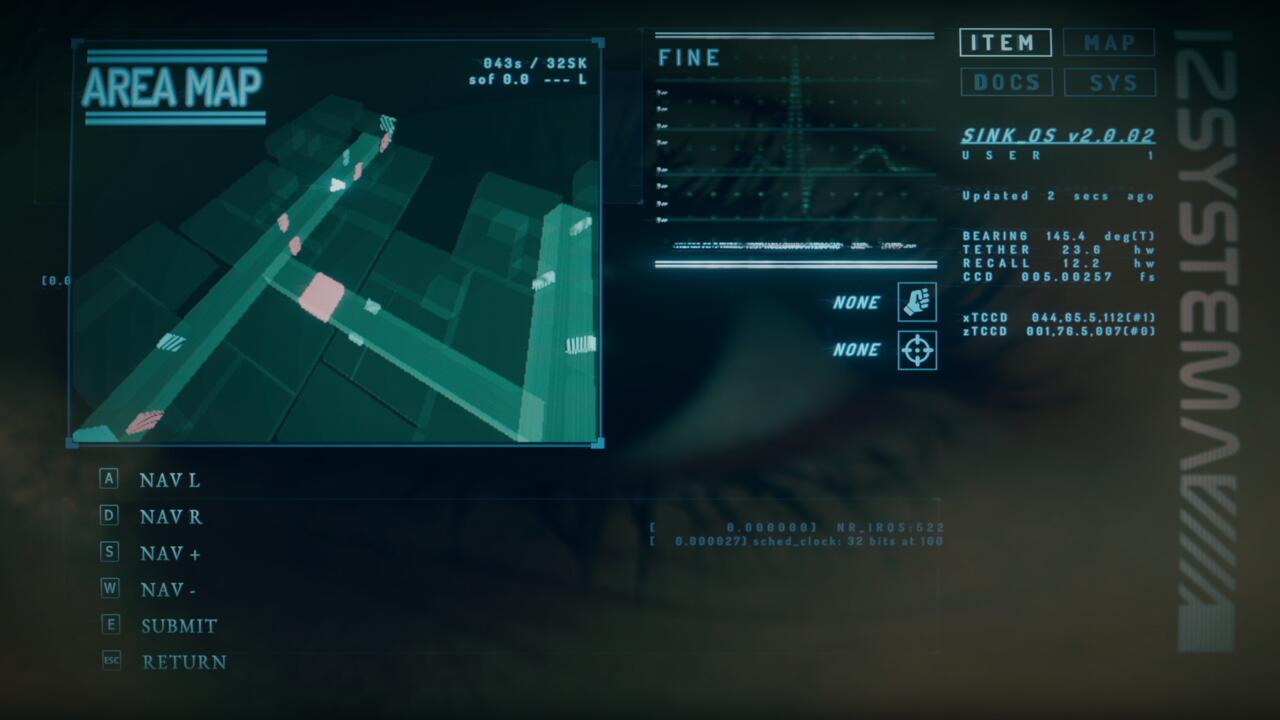

Because the game is shorter than most of those it strives to resemble, some of the genre’s staples are expedited in a way. Puzzles, for example, can be tricky, but never as maddening as Silent Hill 2’s piano puzzle, and often the space and time between finding a puzzle-cracking item and putting it to use is small and short. I actually had to get used to how the pause menu’s map would show me the way forward because I sometimes expected more roadblocks, even as an arrow would essentially tell me, “Go here!” It wasn’t until the back half of the game that I started to trust that the map truly was just pointing me toward the next section, and even when there would be puzzles along the way to unlock that path, all interactable doors were similarly spotlighted on the map.

Like the best Silent Hill games, Hollowbody isn’t just scary; it’s tragic, and the world you’re exploring reminds you of that in every corner. Though even its narrative thread weaves a similar tale–you’re seeking a lost loved one in an eerie town–the thematic elements help Hollowbody rise above facsimile in a manner that its darkened hallways and aggressive monsters sometimes don’t allow. The story is actually set in the future, but the town you explore was abandoned years prior following an apparent bioterror attack. This means you leave a cyberpunk world early on and soon enter a dreary British town hamstrung not just by an attack decades before, but also due to gentrification and abandonment years before that.

Documents scattered across town tell a background plot of townspeople promised an economic stimulus, only to have the rug pulled out from under them in the months and years to come by double-speaking investors. It’s a familiar tale, but not owing to Silent Hill in this case. Instead, it’s pulled from the headlines of the real world, and I appreciate the way Hamley is able to creatively tie an abandoned, monster-infested town to the theme of economic inequality.

Hollowbody is scary, dreary, and sad; it’s all the things I love about horror games. Sometimes, it embodies these feelings because it nearly repurposes the same monsters, places, and predicaments from the games that inspired it. But it’s not all familiar, and the things it does differently are its best attributes, like telling a story conscious of and concerned about sociopolitics and offering a minimalistic but unsettling soundtrack of its own. Maybe the last great Silent Hill game is behind us. I don’t know. But I do know its memory remains alive in successes like Hollowbody.